CJ Johnson’s one man show about controversial German actor Klaus Kinski is undoubtedly gripping. It’s a shame, then, that it’s all for the wrong reasons. Kinski’s life of violent sexual addiction is sure to shock, but when it comes in such an idolised package—when it is presented almost as something to be admired—it becomes much harder to watch.

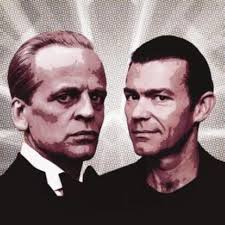

Staged at Holden Street Theatres and directed by Michael Pigott, Johnson has adapted Kinski’s biographies, Kinski Uncut and the rare All I Need is Love, into a performance narrative detailing the actor’s life. Opening with a detailed description of a harrowing trip down the Amazon with director Werner Herzog, it becomes obvious almost immediately that Johnson’s performance as Kinski is not without its problems. He adopts a stereotypical German accent, but the Australian twang can’t help but show its head from time to time. Armed only with his words, instead of drawing the audience into his world he reads the excerpts from Kinski’s autobiography off of a tablet, barely lifting his eyes. The performance loses life this way, coming across like a lecturer philosophising to glassy-eyed students. Thankfully, running silent in the background is a series of film clips accompanying the scenes described. These clips do a good job of filling in the colour to Kinski’s life. On the whole, the lighting and media are executed seamlessly.

Jess Bush accompanies Johnson as Pola, one of Kinski’s daughters. Presented as a face swathed in darkness on a projected screen behind Johnson, like the voice of God she interjects at various points throughout the performance to highlight the reality of Kinski’s impact on the women he surrounded himself with. Bush provides a much-needed female perspective, and she is fantastic, shedding light on Kinski’s decadent lifestyle.

In an industry where a person’s estimable film work cancels out their depravities—Roman Polanski anyone?—it is disappointing to see one such life depicted in a revering light. Kinski, on the evidence of his own writing, is not a good man, wilfully ignoring the suffering of the women around him. Johnson is appropriately gleeful as Kinski describing his sexual encounters, but when he steps out of character that gleefulness, accompanied by admiration, is frustratingly still present. Johnson seems to acknowledge this: he is quoted to say on Kinski and I’s website that Kinski is ‘an incredibly problematic artist to be obsessed with [...] He was a mad, tormented genius, but he may also have been a monster.’ At one point in the performance, while Johnson is the middle of a particularly lurid sexual escapade, the house lights come up and Bush’s voice, clear and condemning, rings out through the theatre: ‘Are you serious?’ It is difficult to gauge whether the show is condemning or venerating Kinski’s life and treatment of women. On this showing alone though it would seem to be the former, which makes the whole experience, unfortunately, too uncomfortable to swallow.